"Born in slavery in Louisiana."

"Born in slavery in Louisiana."

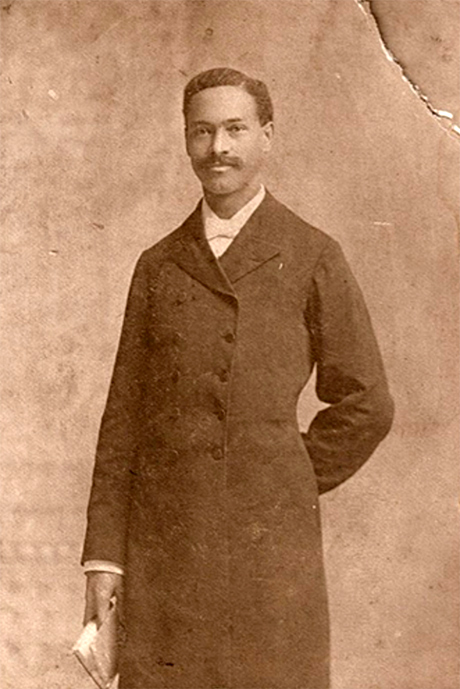

Those are the final words of the 1914 obituary recounting the passing and extraordinary life of Baldwin Wallace University's first known Black graduate, the Rev. Dr. Daniel Webster Shaw.

The death notice in the Oberlin (Ohio) News also proclaims that Shaw, who earned a BA as valedictorian for the then-Baldwin University Class of 1883, "reached a place of honor and great usefulness in his chosen vocation through his own industry and stern effort."

Before he became a noted clergyman and author, Shaw first applied that "industry and stern effort" in the classroom. In fact, his dedication to learning eventually earned him a Doctor of Divinity degree from Wiley College in Texas.

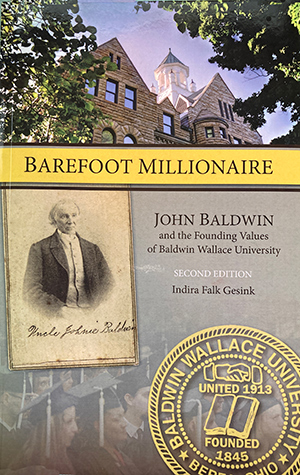

Shaw was one of only six African Americans with doctorates in the entire U.S. at the time, according to BW history professor Dr. Indira Gesink, who told Shaw's story in her book on BW's history and founder, "Barefoot Millionaire."

Gesink notes that Shaw's parents, "a white plantation owner named Percy Shaw and his Black slave wife Harriet," were chronicled in the autobiographical book "12 Years a Slave." His mother was depicted by Alfre Woodard in the 2013 Oscar-winning Best Film by the same name.

Gesink notes that Shaw's parents, "a white plantation owner named Percy Shaw and his Black slave wife Harriet," were chronicled in the autobiographical book "12 Years a Slave." His mother was depicted by Alfre Woodard in the 2013 Oscar-winning Best Film by the same name.

Born four years before the Emancipation Proclamation, Shaw attended school as a young boy near the family's Louisiana plantation.

At age 13, Shaw moved North to enroll in the "preparatory division" at Baldwin University, which was founded 175 years ago as an inclusive institution.

Gesink writes that he "arrived with 20 cents in his pocket" and later took a job as a campus janitor to fund his enrollment in the collegiate division.

Following his graduation at the top of his class, Shaw also studied at Boston University before earning his doctorate.

Shaw went on to serve as a prominent minister to congregations in Baltimore; Pittsburgh; Charleston, West Virginia; Cleveland; and Oberlin. He also held a position on the faculty at Howard University and authored many articles and books.

He was actively engaged in issues of racial equity, and Gesink devotes much of a chapter to delving into Shaw's writings about ongoing segregation and discrimination.

Arguing for Black political independence, he wrote in one pamphlet, "No man is free so long as another commands his action and rules his thought."

Declining health would force Shaw to leave the ministry and return to Oberlin, where he passed away on September 28, 1914.

Shaw may have been BW's first Black graduate, but many others have followed in his footsteps, including such notables as:

More recent grads continue to add their own pages to our state and nation's history, and BW is proud to share and celebrate their achievements year-round on our Alumni Success pages, social media and in other forms of recognition.